Ghosts of Ancient Mesopotamia

Click the image above for the full gallery.

What do you think of when you see the phrase "Ancient Mesopotamia"?

Maybe not a whole lot. It was 4000 BCE—or 6000 years ago, so I'm sure for most of us, our knowledge came from maybe one day of light study in an outdated textbook many years ago.

:: mumbles something incoherent about stone structures in the Middle East ::

Sadly, the above isn't really an exaggeration of what we learn of Ancient Mesopotamia here in the United States. That and…something, something, something…Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

Now, with that bountiful foundation of knowledge and the wonders of the American education system, we know everything there is to know about ancient Mesopotamia. Done.

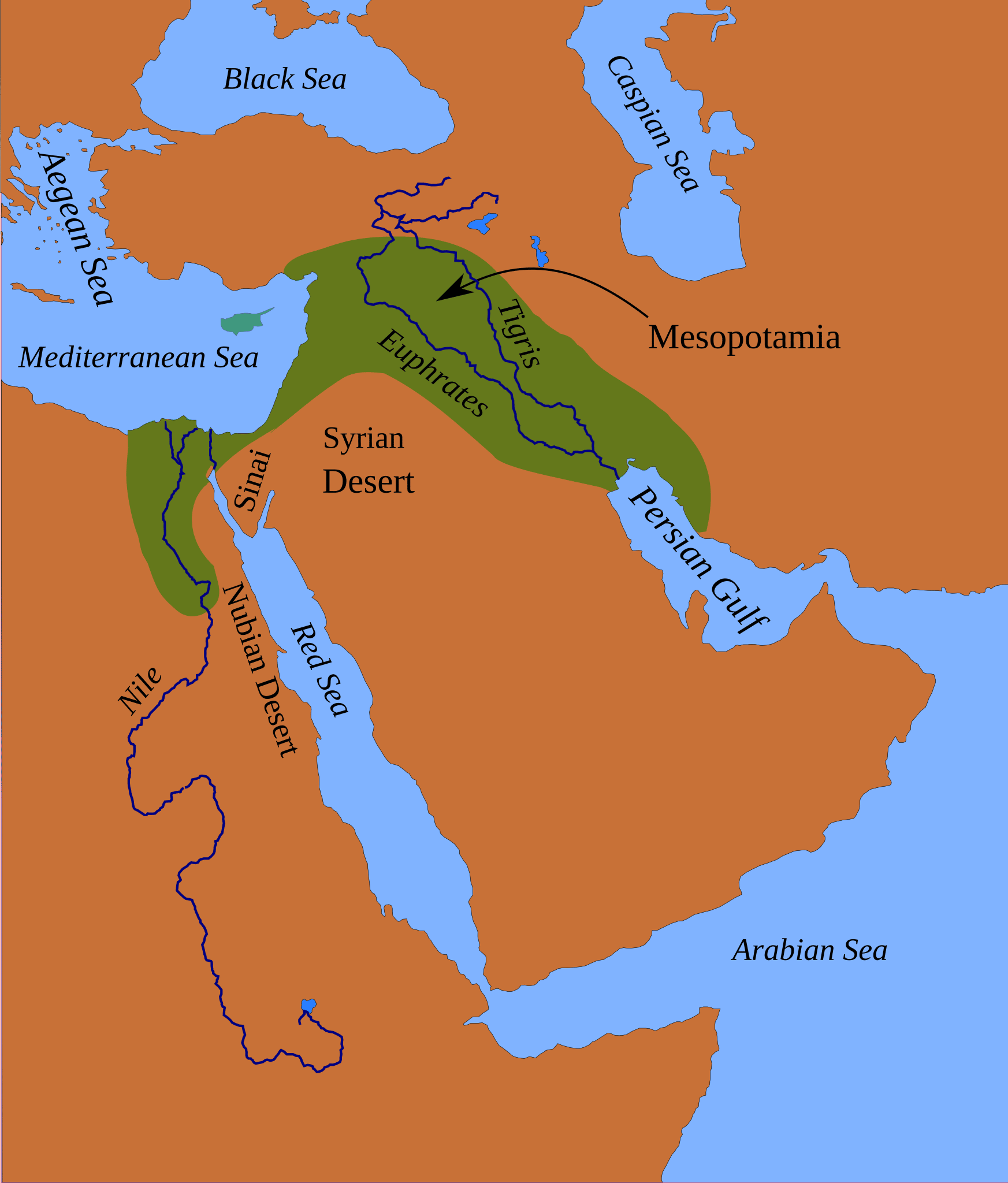

🤨Actually, even with that absolutely massive library of information you have in your head from schooling, there are probably a few things you didn't know about Ancient Mesopotamia. Like 1) that's where ghosts come from and 2) that's where necromancy originated. So, let's fly over (in our mind's imagination) to the Middle East—to modern-day Iraq, along with parts of Syria, Turkey, and Kuwait—where Ancient Mesopotamian civilization once stood.

To a place where the wind stirs the dust of forgotten kings, snaking through crumbled ziggurats and hollows of ancient stone, stirring echoes of voices too old for memory. The air hums—dry, brittle as sun-bleached bone. Somewhere beneath the shifting sands, something stirs.

A shadow clings to the ruins, older than empire and carved from the breath of the dead. The ground tastes of copper and ash, steeped in offerings poured from hands long rotted away. Above, the moon hangs thin and sharp, a sliver of pale judgment watching from a sky the color of burnt slate.

In this place, you walk where the living should not. Each step presses into soft earth packed with centuries of grief, a graveyard forgotten by time but not by those beneath.

The old words are near now.

You can taste them on the wind—bitter as myrrh, heavy with the dead who were never allowed to rest. Times long past tug at you, pulling your senses back, muddying your here and now with there and then…of someone else.

Requiem of Unrest

The sand drinks the blood-red light of dusk as you kneel in the hollow of an ancient temple long since devoured by time. The walls lean inward, pressed by the weight of millennia, their cuneiform prayers worn smooth by nature and neglect. But the words don't need to be seen. They linger here, etched into the air, the dirt, and the marrow of those foolish enough to whisper them aloud.

A human skull lies before you, resting on a cold slab of blackened basalt. It's old. Older than the language that shaped the words coiling in your mouth. A crack snakes through its crown, like something inside once tried to claw its way out.

You can do this.

Bring the dead back.

Bind a spirit into this bone vessel.

Incense burns low, its smoke twisting into shapes the eye refuses to follow. Bitter resin, crushed juniper, and a metallic sting choke the back of your throat. Your pulse syncs with the rhythm of the chant, slow and deliberate. A heartbeat of the dead.

The skull warms beneath your touch.

The small sigils carved into its surface—half-forgotten prayers and threats against the restless—begin to gleam, lines of silver fire racing along paths of ancient fear. You press your thumb into the hollow of one ruined eye socket and feel a pressure push back, a pressure of promises made by desperate men long dead.

The wind dies.

A hiss curls from the space between worlds, not sound but sensation. A cold whisper against your spine. You don't need to look to know that the shadows behind you have deepened, stretching longer than they should, writhing against the flicker of your dying fire.

Words spill from your lips.

An invitation clothed in desperation.

Eṭemmu.

The old word drags its way out of you like a rusted hook through flesh.

Your throat tightens with a creeping cold, and the darkness thickens into shape. A smear of ink against the dim light. It coils around the skull, slipping between the cracks, seeping into the bone like smoke drawn into dry wood.

The words slip from you.

Your chanting falters, lungs burning.

The skull shudders beneath your palm. Cold radiates from within, sinking deep into your muscles and bones. The shadows press against your ribs, slithering behind your eyes. A breathless voice coils through the hollow spaces of your mind—familiar yet impossibly distant.

You called me.

Your fingers won't move.

You brought me back.

A slow scrape—bone on stone.

The skull turns.

I am hungry.

The shadows lash forward, and everything turns to black.

Ghosts of Ancient Mesopotamia

As far as we currently know, the concept of a ghost can be traced back to the people of Ancient Mesopotamia. In Ancient Mesopotamia, death marked a transformation, entering another state of existence.

The people of Sumer, Akkad, Babylon, and Assyria believed that after death, the spirit—eṭemmu—separated from the body but continued on, requiring offerings from the living to remain at peace. Without proper rites or remembrance, these spirits returned to disrupt the world of the living. Imagine waking in the cold void of Kur—your body forgotten, your name erased, and every hunger gnawing at what remains of you. An eternity spent as a husk of your former self, clawing at the edges of a world that no longer remembers you exist. Sound familiar? That same fear from ancient times still haunts our ghost stories of today.

In Sumerian, the underworld, Kur, was a cold, dark realm—like a cave—where spirits continued experiencing a hollow version of life. The food and drink of Kur were dry dust, and only offerings from the world of the living provided real sustenance.

In texts like The Descent of Inanna (c. 1900–1600 BCE), even gods feared the desolation of Kur. This Sumerian poem chronicles the journey of Inanna, the great goddess and Queen of Heaven, as she descends from her celestial realm to earth and into the underworld to visit her widowed sister, Ereshkigal, Queen of the Dead.

The dead relied on offerings of fresh food, water, beer, and honey from surviving family members. If those offerings were ignored (or there were no surviving family to fulfill the duties), or the graves left untended, the spirits became restless and sometimes forced their way back into the realm of the living in a way that we would—today—know as a haunting. It was even more likely to happen for the dead who weren't buried or whose bodies didn't receive proper rites of passage. Bleaker still, there was no final judgement for the dead—no reward or punishment for how they lived, just the hollow persistence of unlife.

Judgement vs judgment

Yeah…so I learned while writing that the word's US spelling is "judgment" without the 'E' and the British spelling is "judgement" with the E. I caught my spell checker sneakily removing the E without telling me. I put it back because the word spelled without the E looks very, very wrong to me. I wonder how often my US English spellchecker has made these changes without telling me.🧐

Anyway, back to Mesopotamia—where the spelling didn't matter nearly as much as keeping the dead from crawling back for dinner.

In Ancient Mesopotamian belief, spirits were categorized by how they died and how their bodies were treated. Those granted proper funerary rites remained in the underworld. Others—especially those who died violently, were improperly buried, or lacked descendants to honor them (causing a severe cosmic imbalance)—ended up wandering the earth. These wandering spirits caused illness, madness, and misfortune, punishing the living for their neglect—much like the modern concept of poltergeists or troublesome ghosts with unfinished business.

Interestingly, ancient texts describe how neglected spirits demanded what was denied to them in death. Their pleas were direct and quite unsettling if you take a moment to think of what it would be like to hear a disembodied voice say these things to you.

"Let me eat with you."

"I am thirsty. Let me drink with you."

"I am cold. Let me get dressed with you."

These descriptions from ancient texts align closely with the more contemporary idea of hungry ghosts. And, like the ancient stories, hungry ghosts become malevolent without offerings from the living.

Exorcists, called āšipu, performed rituals to address the danger posed by these restless spirits. Their rites required precise incantations, ritual offerings, and protective symbols to pacify or expel ghosts. Objects like clay figurines, inscribed tablets, or skulls could trap dangerous spirits, keeping them bound. A single mistake could lead to possession, illness, or even death.

Sometimes, necromantic rituals were performed to communicate with or summon spirits, often to seek knowledge, protection, or answers the living could not provide. These ceremonies were risky and frequently tied to the practice of kispum—a ritual offering to appease or invoke ancestral spirits. Practitioners followed strict procedures to prevent unintended consequences, drawing from incantations inscribed on cuneiform tablets, which called upon gods like Nergal or Ereshkigal to bind or pacify the dead. These rites were not undertaken lightly; each interaction with the spirit world was deliberate, fraught with mortal danger, and carried the constant threat of possession, illness, or worse—just like the story above.

Ancient Mesopotamians also feared premature burial—a horror reflected in texts where individuals, thought dead but still alive, faced the terror of waking entombed in darkness. Again, another aspect from thousands of years ago that's particularly intriguing is that the same fear lives on today and is still depicted in modern media.

And, much like today, in times of conflict, even political power could extend to the dead. Some Assyrian kings ordered the desecration of enemy graves, scattering bones to sever spiritual ties and condemn rivals' spirits to perpetual unrest.

Assuming the ancient beliefs about ghosts are true, we're all fucked. No, really. Because that means our modern world is haunted by thousands of years of neglect. Rituals have long since faded, and the forgotten dead, once nourished by offerings and respect, now lie in silence beneath cities and fields. Their unrest may stir in ways humanity no longer recognizes—manifesting as subtle misfortunes, unexplained sicknesses, or a persistent sense that something unseen still lingers, waiting for debts long unpaid to be acknowledged. The dead may no longer speak, not because they are silent, but because we've forgotten the language of listening—something we seem to have lost not just with the dead but with the world itself.

Relevant & Related

- Pick up a copy of The First Ghosts: Most Ancient of Legacies by Irving Finkel to explore humanity's earliest ghost stories, focusing on Mesopotamian beliefs and practices.

- While you're at it, grab The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion by Thorkild Jacobsen for a solid foundation of Mesopotamian spiritual beliefs, including the role of the underworld and its connection to the living.

- And, because I know you love books... The Sumerian World by Harriet Crawford.

- Check out The British Museum's website for information and even a virtual tour of their exhibit on Mesopotamia.

- For more museum goodness, take a look at the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures at The University of Chicago and their Highlights from the Collection: Assyria.

- Even more pictures and exhibits over on The Louvre's site.

- Videos more your thing? Try The British Museum's YouTube Channel. You can even see Irving Finkel discussing How to perform necromancy involving a ghost and a skull.

- Also, try Digital Hammurabi, a YouTube channel run by Assyriologists that offers in-depth explanations of Mesopotamian culture, religion, and language.

- Interested in cuneiform? There's a site for that, too. CDLI (Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative) is a searchable database of cuneiform texts from Mesopotamia.

You might enjoy these other articles: